| General relativity |

|---|

| Introduction Mathematical formulation Resources |

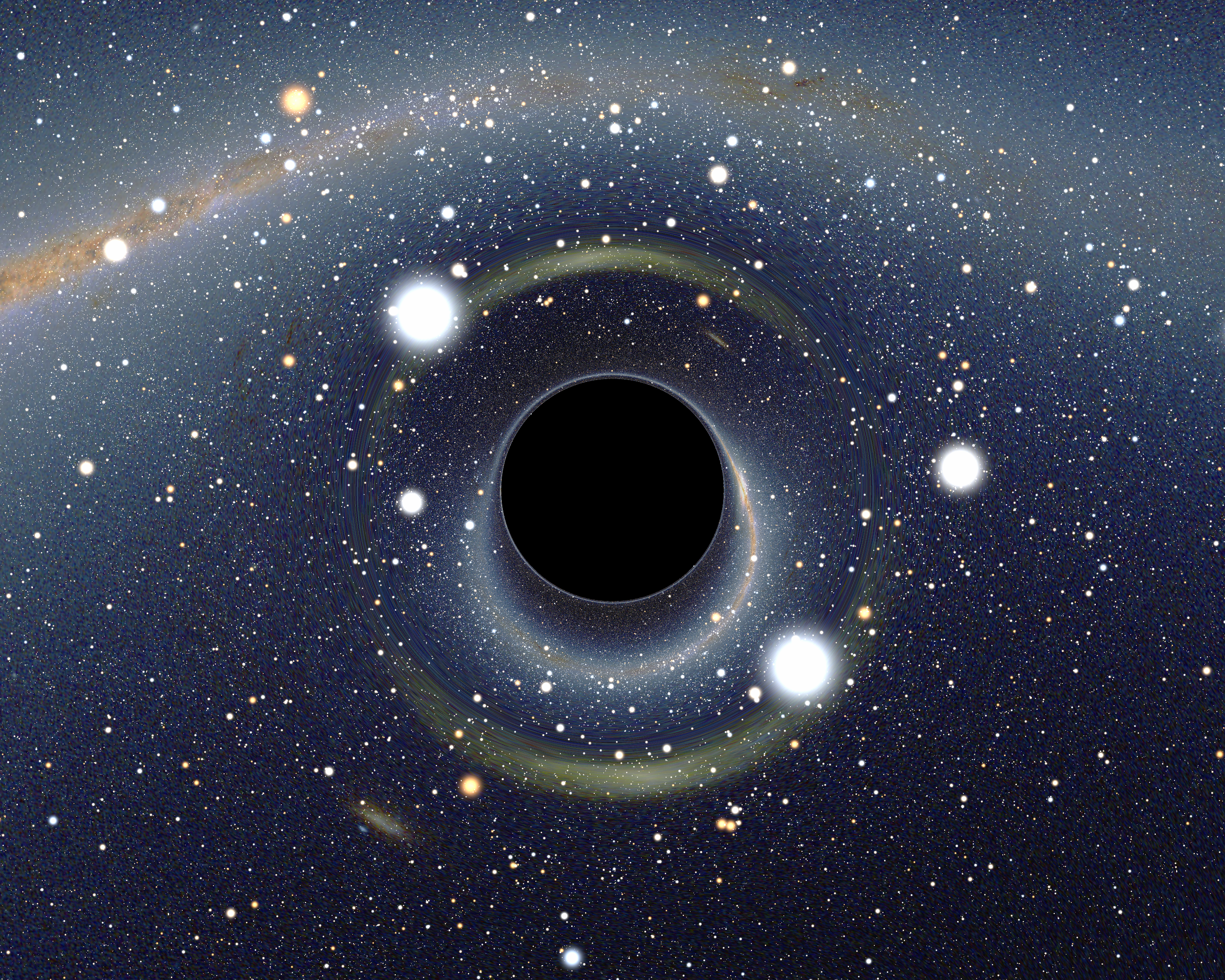

A black hole is a region of spacetime from which nothing, not even light, can escape.[1] The theory of general relativity predicts that a sufficiently compact mass will deform spacetime to form a black hole. Around a black hole there is a mathematically defined surface called an event horizon that marks the point of no return. It is called "black" because it absorbs all the light that hits the horizon, reflecting nothing, just like a perfect black body in thermodynamics.[2] Quantum mechanics predicts that black holes emit radiation like a black body with a finite temperature. This temperature is inversely proportional to the mass of the black hole, making it difficult to observe this radiation for black holes of stellar mass or greater.

Objects whose gravity field is too strong for light to escape were first considered in the 18th century by John Michell and Pierre-Simon Laplace. The first modern solution of general relativity that would characterize a black hole was found by Karl Schwarzschild in 1916, although its interpretation as a region of space from which nothing can escape was not fully appreciated for another four decades. Long considered a mathematical curiosity, it was during the 1960s that theoretical work showed black holes were a generic prediction of general relativity. The discovery of neutron stars sparked interest in gravitationally collapsedcompact objects as a possible astrophysical reality.

Black holes of stellar mass are expected to form when massive stars collapse in a supernova at the end of their life cycle. After a black hole has formed it can continue to grow by absorbing mass from its surroundings. By absorbing other stars and merging with other black holes, supermassive black holes of millions of solar masses may be formed.

Despite its invisible interior, the presence of a black hole can be inferred through its interaction with other matter. Astronomers have identified numerous stellar black hole candidates in binary systems, by studying their interaction with their companion stars. There is growing consensus that supermassive black holes exist in the centers of most galaxies. In particular, there is strong evidence of a black hole of more than 4 million solar masses at the center of our Milky Way.

History

The idea of a body so massive that even light could not escape was first put forward by geologist John Michell in a letter written to Henry Cavendish in 1783 of the Royal Society:

If the semi-diameter of a sphere of the same density as the Sun were to exceed that of the Sun in the proportion of 500 to 1, a body falling from an infinite height towards it would have acquired at its surface greater velocity than that of light, and consequently supposing light to be attracted by the same force in proportion to its vis inertiae, with other bodies, all light emitted from such a body would be made to return towards it by its own proper gravity.—John Michell[3]

In 1796, mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace promoted the same idea in the first and second editions of his book Exposition du système du Monde (it was removed from later editions).[4][5] Such "dark stars" were largely ignored in the nineteenth century, since it was not understood how a massless wave such as light could be influenced by gravity.[6]

General relativity

In 1915, Albert Einstein developed his theory of general relativity, having earlier shown that gravity does influence light's motion. Only a few months later, Karl Schwarzschild found a solution to Einstein field equations, which describes the gravitational field of a point mass and a spherical mass.[7] A few months after Schwarzschild, Johannes Droste, a student of Hendrik Lorentz, independently gave the same solution for the point mass and wrote more extensively about its properties.[8] This solution had a peculiar behaviour at what is now called the Schwarzschild radius, where it became singular, meaning that some of the terms in the Einstein equations became infinite. The nature of this surface was not quite understood at the time. In 1924, Arthur Eddington showed that the singularity disappeared after a change of coordinates (see Eddington–Finkelstein coordinates), although it took until 1933 for Georges Lemaître to realize that this meant the singularity at the Schwarzschild radius was an unphysical coordinate singularity.[9]

In 1931, Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar calculated, using special relativity, that a non-rotating body of electron-degenerate matter above a certain limiting mass (now called theChandrasekhar limit at 1.4 solar masses) has no stable solutions. [10] His arguments were opposed by many of his contemporaries like Eddington and Lev Landau, who argued that some yet unknown mechanism would stop the collapse.[11] They were partly correct: a white dwarf slightly more massive than the Chandrasekhar limit will collapse into a neutron star,[12]which is itself stable because of the Pauli exclusion principle. But in 1939, Robert Oppenheimer and others predicted that neutron stars above approximately three solar masses (theTolman–Oppenheimer–Volkoff limit) would collapse into black holes for the reasons presented by Chandrasekhar, and concluded that no law of physics was likely to intervene and stop at least some stars from collapsing to black holes.[13]

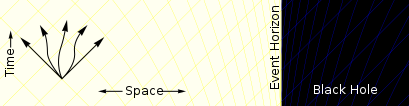

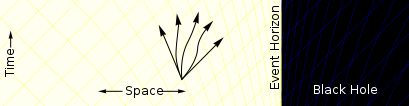

Oppenheimer and his co-authors interpreted the singularity at the boundary of the Schwarzschild radius as indicating that this was the boundary of a bubble in which time stopped. This is a valid point of view for external observers, but not for infalling observers. Because of this property, the collapsed stars were called "frozen stars,"[14] because an outside observer would see the surface of the star frozen in time at the instant where its collapse takes it inside the Schwarzschild radius.

Golden age

In 1958, David Finkelstein identified the Schwarzschild surface as an event horizon, "a perfect unidirectional membrane: causal influences can cross it in only one direction".[15] This did not strictly contradict Oppenheimer's results, but extended them to include the point of view of infalling observers. Finkelstein's solution extended the Schwarzschild solution for the future of observers falling into a black hole. A complete extension had already been found by Martin Kruskal, who was urged to publish it.[16]

These results came at the beginning of the golden age of general relativity, which was marked by general relativity and black holes becoming mainstream subjects of research. This process was helped by the discovery of pulsars in 1967,[17][18] which were shown to be rapidly rotating neutron stars by 1969.[19] Until that time, neutron stars, like black holes, were regarded as just theoretical curiosities; but the discovery of pulsars showed their physical relevance and spurred a further interest in all types of compact objects that might be formed by gravitational collapse.

In this period more general black hole solutions were found. In 1963, Roy Kerr found the exact solution for a rotating black hole. Two years later, Ezra Newman found the axisymmetricsolution for a black hole that is both rotating and electrically charged.[20] Through the work of Werner Israel,[21] Brandon Carter,[22][23] and David Robinson[24] the no-hair theorememerged, stating that a stationary black hole solution is completely described by the three parameters of the Kerr–Newman metric; mass, angular momentum, and electric charge.[25]

For a long time,[vague] it was suspected that the strange features of the black hole solutions were pathological artifacts from the symmetry conditions imposed, and that the singularities would not appear in generic situations. This view was held in particular by Vladimir Belinsky, Isaak Khalatnikov, and Evgeny Lifshitz, who tried to prove that no singularities appear in generic solutions. However, in the late sixties Roger Penrose[26] and Stephen Hawking used global techniques to prove that singularities are generic.[27]

Work by James Bardeen, Jacob Bekenstein, Carter, and Hawking in the early 1970s led to the formulation of black hole thermodynamics.[28] These laws describe the behaviour of a black hole in close analogy to the laws of thermodynamics by relating mass to energy, area to entropy, and surface gravity to temperature. The analogy was completed when Hawking, in 1974, showed that quantum field theory predicts that black holes should radiate like a black body with a temperature proportional to the surface gravity of the black hole.[29]

The term "black hole" was first publicly used by John Wheeler during a lecture in 1967. Although he is usually credited with coining the phrase, he always insisted that it was suggested to him by somebody else. The first recorded use of the term is in a 1964 letter by Anne Ewing to the American Association for the Advancement of Science.[30] After Wheeler's use of the term, it was quickly adopted in general use.

Properties and structure

Physical properties

Event horizon

Singularity

Photon sphere

Ergosphere

Formation and evolution

Gravitational collapse

Primordial black holes in the Big Bang

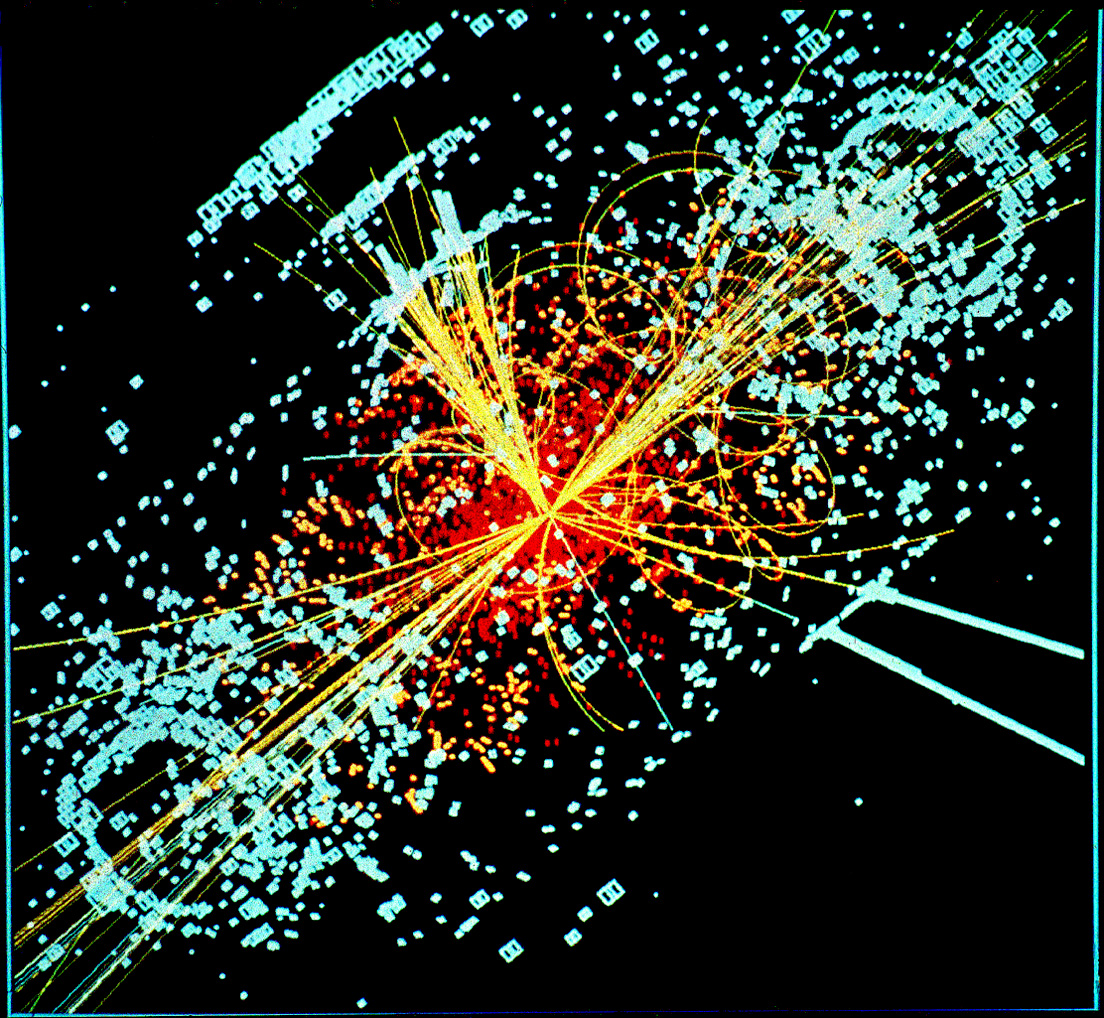

High-energy collisions

Growth

Evaporation

Observational evidence

Accretion of matter

X-ray binaries

Quiescence and advection-dominated accretion flow

Quasi-periodic oscillations

Galactic nuclei

Gravitational lensing

Alternatives

Open questions

Entropy and thermodynamics

In 1971, Hawking showed under general conditions[Note 3] that the total area of the event horizons of any collection of classical black holes can never decrease, even if they collide and merge.[112] This result, now known as the second law of black hole mechanics, is remarkably similar to the second law of thermodynamics, which states that the total entropy of a system can never decrease. As with classical objects atabsolute zero temperature, it was assumed that black holes had zero entropy. If this were the case, the second law of thermodynamics would be violated by entropy-laden matter entering a black hole, resulting in a decrease of the total entropy of the universe. Therefore, Bekenstein proposed that a black hole should have an entropy, and that it should be proportional to its horizon area.[113]

The link with the laws of thermodynamics was further strengthened by Hawking's discovery that quantum field theory predicts that a black hole radiates blackbody radiation at a constant temperature. This seemingly causes a violation of the second law of black hole mechanics, since the radiation will carry away energy from the black hole causing it to shrink. The radiation, however also carries away entropy, and it can be proven under general assumptions that the sum of the entropy of the matter surrounding a black hole and one quarter of the area of the horizon as measured in Planck units is in fact always increasing. This allows the formulation of the first law of black hole mechanics as an analogue of the first law of thermodynamics, with the mass acting as energy, the surface gravity as temperature and the area as entropy.[113]

One puzzling feature is that the entropy of a black hole scales with its area rather than with its volume, since entropy is normally an extensive quantity that scales linearly with the volume of the system. This odd property led Gerard 't Hooft and Leonard Susskind to propose the holographic principle, which suggests that anything that happens in volume of spacetime can be described by data on the boundary of that volume.[114]